Is Safta Yaffa’s Baharat Still Fresh After 17 Years in the Freezer?

Artwork by Danni Sigler.

By LeeEl Yehezkel

How a frozen box of spices carried memories across three generations.

Two years ago, I received a gift from my grandmother. It was a small tupperware of my great-grandmother Yaffa’s— born as Georgiya— hand-mixed baharat spice mix. Savta Yaffa died in 2008.

The last time I saw her was in 2005, when I last visited Israel. My only memories of my great-savta Yaffa are from when I was eight years old; I remember the trees in her yard, and how I used to take bucket baths outside while my savta Zahava showered us with a hose. The itchy, old-fashioned couches on which we slept, a tea garden, and my newborn cousin, Noee, how small her nose, hands, and feet were. I remember Savta Yaffa sitting silently in the kitchen. Beyond that, I don’t remember much. My childhood memories of her are painted in watercolor; Israel itself almost felt like Narnia, a far-away land my parents came from, where people only spoke Hebrew, drank tea from herbs in the garden, and where other Iraqi Jews existed outside of my family.

Great-Safta Yaffa’s frozen baharat mix.

On the other side of the world was my “real” life in California. There, Jews spoke English and “ate bagels” (though I didn’t understand that bagels were, allegedly, “Jewish” until my early 20’s). Many of their family names ended in “berg’ or “man” or “stein,” unless they were Persian. None of them had a family name resembling “Yehezkel”.

Truthfully, at the time, I didn’t identify myself as anything other than Ashkenazi— that was the Jewish world around me. I was barely aware that my family was Iraqi, or that there was such a thing as Iraqi Jewish history. My grandfather never spoke about it except when telling terrible stories of barely surviving an antisemitic stoning attack at six years old. I am told by a close friend that drinking loose-leaf tea in glasses is a distinctly “Iraqi” thing, due to British influence during the Mandate. I don’t know if that is true, but I suppose I did grow up drinking a lot of loose-leaf tea from the garden.

Only in high school, the first time I studied at a non-Jewish school, did I first claim my Iraqi roots. A high school frenemy had spoken about being Middle Eastern, and I piped up. “I’m Middle Eastern too!” I said. He disagreed. “You can’t claim an identity just because your ancestors were there 2,000 years ago.” I told him that my grandfather speaks Arabic natively, that my family in Israel are only one or two generations displaced from Iraq. In hindsight, I understand that I never needed to prove myself. Even if I didn’t grow up eating my Savta Yaffa’s t’beet every Shabbat.

That t’beet is the recipe for which I have been saving Savta Yaffa’s baharat over the past two years. My grandfather’s sister, Dina, used to invite me over for Friday night dinner every time she was doing a “Shabbat t’beet” or “Shabbat sambousak.” If I couldn’t make it that weekend, she would wait to make it for a Shabbat where I could come. Now that Dina has passed, no one else has made Savta Yaffa’s t’beet recipe. For the past two years, I have been tempted to make it myself, but I worry that her special baharat mix will have become stale after all those decades in the freezer.

The baharat of my ancestors— literally, from three generations before me— has sat untouched in my grandmother’s freezer for fifteen years, and in mine for two. Possibly, the last hands that touched said baharat were those of my great-savta Yaffa. Did she mix the spices herself, or did she instruct the spice merchant on what to add? I imagine my grandparents opening her spice cabinets in the week that she died unexpectedly from an infuriating incident of medical malpractice. Those jars of fresh spices were mixed with the expectation of many more home-cooked meals for her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. They were not meant to be frozen for decades. Maybe, I thought, I could meet those expectations. I resolved to try, at least.

At the butcher’s, I requested two enormous turkey necks and told him I’m making t’beet.

“You’re making t’beet?”, he asked incredulously.

“Yes, and you’ll be surprised to know that I’m actually Iraqi.” I replied with a smile. A sentence I have repeated a thousand times before. This line of questioning has always baffled me: do people think that cooking choices or skills are predetermined at birth? What have I actually inherited from Iraq, other than a last name, traumatic stories, and a box of seventeen-year-old spices? Truthfully, I have always felt like an imposter, deeply insecure about if I am “enough” of an Iraqi Jew, if by being brought up in the U.S. and far from my culture invalidates it. Much of the reason I have learned to cook so many Iraqi dishes over the years, read stories of Iraqi Jews, watch documentaries, written essays, interrogated my aunt Dina, and constantly told others where my name comes from is out of that sense of insecurity. Desperation, too, that it won’t one day all disappear.

But I write now about cooking t’beet with Savta Yaffa’s baharat. One of my aunts, Orly, compiled all of her handwritten recipes and sent them to me. My grandmother Zehava guides me over the phone— she learned to cook t’beet from her mother-in-law, Savta Yaffa herself.

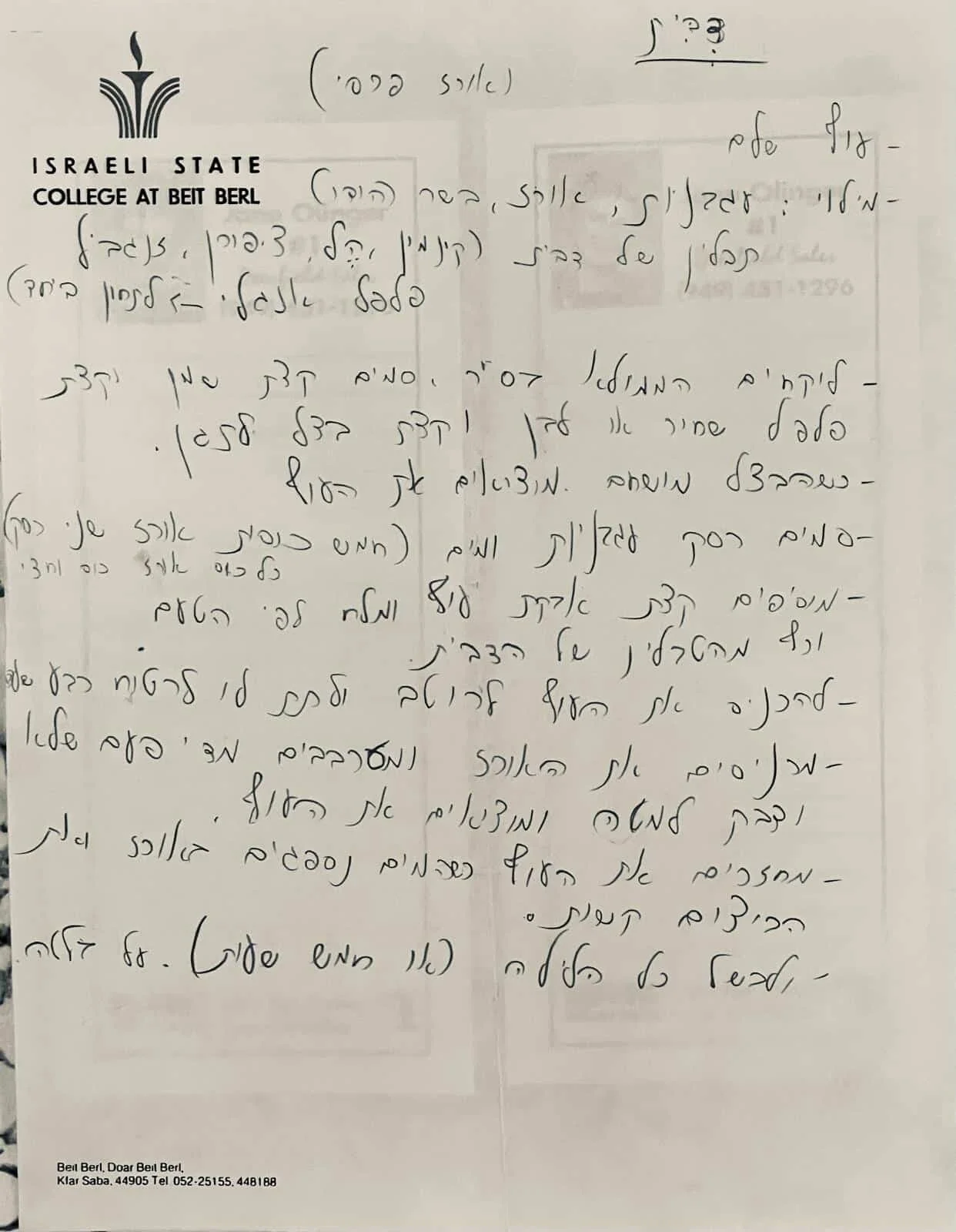

Safta Yaffa’s t’beet recipe.

Since I have decided not to commit to stuffing a whole chicken, but rather cook the version with turkey necks, the recipe is surprisingly simple. Savta Yaffa’s baharat smells amazing. I cannot help but add several more teaspoons of the mix than necessary out of sheer excitement. And as I had expected, it does smell different from store-bought baharat. ‘Baharat’ simply means ‘spices’ in Arabic, so the precise mix of spices varies widely between regions. This baharat smelled of nutmeg, cinnamon, saffron, cardamom, and English pepper. Upon smelling it, I was flooded with memories of my great-aunt Dina calling me to ask if I was coming for Shabbat; because if so, she was planning on cooking a proper Iraqi Shabbat meal for me.

I put the pot of t’beet into my sister’s oven and set a timer for eight hours of slow cooking. Tomorrow, there would be an enormous pot of rice and chicken waiting to be devoured. Whether it would resemble Savta Yaffa’s t’beet, I had no idea. With that, I set an alarm for myself; the t’beet and I would wake together.

The following morning, I removed the pot from the oven and set it on the counter to cool down. My nerves got the better of me and I was not the first to taste it. Rather, it was my sister who took the first bite of meat and potatoes from the dish. Only when she proclaimed it delicious, did I find within myself the courage to taste it myself.

The t’beet, fresh from the oven.

I couldn’t remember the precise texture of Dina’s t’beet, nor its aroma or consistency, but I was fairly sure that this was what t’beet was supposed to taste like… the slow-cooked rice was brown and mushy, almost like a porridge. The turkey neck meat slid off the bone with ease, and the eggs were a light shade of brown. The flavor of Savta Yaffa’s baharat had not faded with the years— on the contrary, it was as strong as ever. The scent though, is what stopped me in my tracks.

Seventeen years had passed, but my sister’s kitchen now smelled like Savta Yaffa’s— as if she had just stepped out of the room. •

Recipe for Safta Yaffa’s T’beet:

Whole chicken, stuffed

Stuffing: tomatoes, Persian rice, meat (turkey).

T’beet baharat: (cinnamon, cardamom, cloves, saffron, English pepper) Grind together.

Put stuffed chicken in a pot, add oil, and some black or white pepper, and sauté some onions.

When the onion is browned, remove chicken from pot.

Add tomato puree and water (5 cups of rice, 2 cups of purée).

Add some chicken bouillon powder and salt according to taste; add a spoon of the baharat mix.

Place chicken in the sauce and let it boil for 15 min.

Add the rice and stir every so often so that it doesn’t stick to the bottom, and then out the chicken; add it back into the pot, along with some hardboiled eggs, once the rice has absorbed the water.

Cook all night (or 5 hours) al-balata (traditionally the stone floor of an oven, or if you don’t have a traditional tannur, on low heat, covered.

NOTE: Savta also made a version of this recipe with stuffed turkey necks instead of stuffed chicken. This is the version I made.

LeeEl Yehezkel is an Israeli-American living in Israel, studying an M.sc. in Environmental Quality at the Technion. She is of both Ashkenazi (Romania and Slovakia) and Mizrahi (Iraqi) descent, and this family history deeply informs how she sees the world and her writing.