The Ghosts of Hartuv

In Israel's Judean hills, two infamous sites— the ruins of Hartuv and nearby Zekharia's abandoned mosque— tell intersecting stories of loss, memory, and the complexity of Jewish and Arab relations.

It would be easy to pass by the grounds of the Hartuv Museum without realizing what once stood there. The museum itself sits far behind a rusting iron gate, its yard overgrown with trees and fallen leaves. If not for the small sign that hangs at its entrance, I wouldn’t have known it was a museum at all.

As I began to look for the entrance of the museum, faded memorial stones marked my path— one for Hartuv, and another for the Lamed-Heh Convoy disaster, where thirty-five young Palmach soldiers were ambushed and killed by Arab villagers and guerilla fighters on their way to bring supplies to the besieged villages of Gush Etzion in 1948. The doors to the museum were locked; when I called the number listed on Google Maps, Yael Kenan answered, the founder of the museum from 1968. She quickly arranged for one of her colleagues to give me a private tour.

The museum itself is one small room, once a stone barn from the original moshava of Hartuv. The floor is uneven, the ceiling low, its walls lined with photographs, faded newspaper clippings, and letters. Inside, Yael’s colleague Rachel begins to tell the story of Hartuv, an unbelievable saga of survival and collapse that unfolded over some sixty-five years on this small patch of land.

Over the decades, Hatuv’s ownership had changed hands again and again. It had first belonged to a Spanish ambassador who leased it to Arab tenants; then, it was sold to an English missionary group that brought in destitute Romanian Jews, offering them homes on the condition that they attend Sunday services (within a few years, most had left, refusing to convert). Bulgarian Sephardic Jews, then, bought the land from the missionaries and established the first Sephardic Jewish settlement in Ottoman Palestine, inspired by Rabbi Yehuda Alkalai— who Herzl himself later cited as an early influence— and fleeing the brutal pogroms that had shaken Jewish life in Bulgaria. After years of incredible hardship, the Bulgarians built a modest agricultural settlement that visionaries like Bialik, Kipnis, and Dizengoff visited, drawn to its beauty and renewal.

This all took place decades before 1929, when Arab riots destroyed, looted, and burned Hartuv to the ground. After being rebuilt, it would fall once again amidst the battles of 1948. It is primarily (and most infamously) known for the Lamed-Heh Convoy disaster.

All of it— the faith, the triumph and failure and hardships, the violence, the ideologies and loss that defined the land from the late 19th century to 1948— was compressed here into one hillside, one forgotten museum behind a rusting gate. I felt that I was standing in a microcosm of Israel’s story, condensed into a few square meters of a former moshava barn, the only building left standing from Hartuv.

“Are there any other interesting historical sites in this area?” I ask Rachel. She tells me that only a few kilometers away, in Moshav Zekharia, are the ruins of a mosque.

When I visit a week later, I am surprised to see that the mosque is quite literally in the center highest point of the moshav, and many houses overlook it. It is fenced off, with signs warning of danger, the entrance covered with overgrown bushes.

Only later in my research do I realize how deeply interconnected the story of Zekharia is with Hartuv. After the Lamed-Heh disaster, Haganah forces punitively attacked surrounding Arab villages, including the Zekharia’s predecessor, Zakariyya. By 1950, any Arab residents that had not already fled from there were expelled to Ramla, or the West Bank.

Zvi Yehezkeli, one of Israel’s leading commentators on Arab affairs, describes a moment back in 2000, when a group of Palestinians from the Dheisheh refugee camp arrived by bus to Moshav Zekharia. They said that they came to see their houses, and asked if they could pray in the mosque. “Yes,” the Jewish residents told them, “The mosque is fenced off and collapsing, but you’re welcome to pray.”

Afterwards, as the Palestinian group and Jewish residents began to mingle, the conversation quickly devolved into shouting. The Palestinians insisted that they wanted to return; and the Jews said that these were their homes.

I decided I need to speak with Yael.

At eighty years old, Yael Kenan has lived in her Jerusalem apartment for over fifty years. Her home is covered with artwork. Books, maps, plants, and photographs burst from her selves, and she herself bubbles with excitement upon meeting me. After half an hour of watching her run up and down the stairs to bring out plates of fruits, cake, and tea, we finally sit down and begin to talk.

The year was 1965. She was eighteen years old, fresh out of her teaching seminar, Yael came to Moshav Naham– next to the ruins of Hartuv— to help build a school for immigrant youth from Morocco, Yemen, and Cochin. It was there that she first met Ben-Zion, an elderly man who lived alone in a wooden hut near the fields. He was born on this land, he told her. His family had left for Tel Aviv during the war, but he had refused. The dilapidated ruins of homes around him, he said, had once belonged to his neighbors and relatives, Sephardic Jews from Bulgaria that had lived there, in Hartuv, until 1948. But after the war, the government had told them not to return.

That conversation, Yael told me, changed her life. Soon after, she began studying and teaching the story of Hartuv at the high school she helped establish in Naham, Even HaEzer. Yael’s storytelling is non-linear, looping back a few decades or jumping forward in time while in the middle of a story in order to give any extra anecdote or context.

She apologizes more than once for digressing, asking if I was okay on time. “If I’m going to tell the story,” she said, “I have to tell everything.”

Only a day before Hartuv was evacuated in 1948, she said, Gush Etzion had fallen. Hartuv’s residents were led out secretly at night— and in complete silence— towards the nearby Jewish village of Kfar Uriya, passing Arab villages along the way. Among them was a baby who had been given a sedative so he wouldn’t make noise, when suddenly, he awakened and began to cry. In real life, Yael said, one of the residents fleeing Hartuv simply took him to the side and hushed him back to sleep, but later on, the famous writer Abba Kovner retold it as “Operation Baby.” In his more dramatic rendition, the commander leading the families of Hartuv to safety shouted, “Kill the boy, because if not, all of us will die!” Yael chuckled. “This wasn’t true,” she said, “but a story is a story.” Kovner was a survivor of the Holocaust, and his rendition must have captured the existential urgency and trauma that defined Jewish communities after the Holocaust, and certainly during the 1948 war.

Still, she said, the descendants of Hartuv do not like his story very much.

When I ask her if she knows anything about the mosque in Zekharia, she rushes to take out an encyclopedia-like book on ancient and modern Israel; it describes the name for an Arab village at the foot of the Judean mountains, within the boundaries of today’s Moshav Zekharia. The Arabs, the book writes, attribute it to Zachariah, the father of John the Baptist, who is also mentioned in the Quran. Nothing else is written.

I tell Yael that I tried to join Arabic Facebook groups of descendants from the village of Zakariyya to learn more but wasn’t accepted— and she laughs. I ask her why she thinks the stories of Hartuv are important for young people to know, and she says it’s because they show how fragile and complex Jewish and Arab relations were in the past.

Then she tells me one last story.

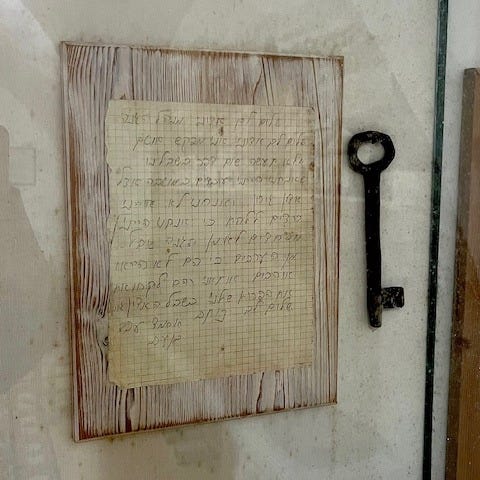

Of everything in the museum, Yael says, two objects matter the most: a letter and key, framed in a glass case. The letter, written in Hebrew in 1948 by an Arab boy named Ahmad living near Hartuv, read: “To the honorable commander of the Haganah, please, do not harm my family. We are loyal to the unit and behaved as good people. We have not done harm to Jews and we do not want war. I ask you to protect us and our home.” He left it in the keyhole of a chicken coop in Hartuv, where a journalist later found it. Years later, he gave it to Yael when she opened the Museum.

Yael was stunned. She wondered— how did this boy learn Hebrew?

And she learned that the person who taught him Hebrew, in fact, was the daughter of Ben-Zion, the man she first learned Hartuv’s story from. To her, it was evidence that relationships between Jews and Arabs in Hartuv were more complicated than she had originally thought.

“If he wanted to learn Hebrew,” Yael said, “then I thought he must have been a smart boy.” It took years, but she eventually tracked him down— he was a doctor, living in Bethlehem. They spoke once on the phone and arranged to meet for coffee in Jerusalem; but the day they were supposed to meet, the First Intifada broke out. He then called her and said, “Please don’t contact me anymore.”

Yael paused. “Stories,” she said, “stories.” •